Personal Table Service of the Emperor

Sèvres manufactory

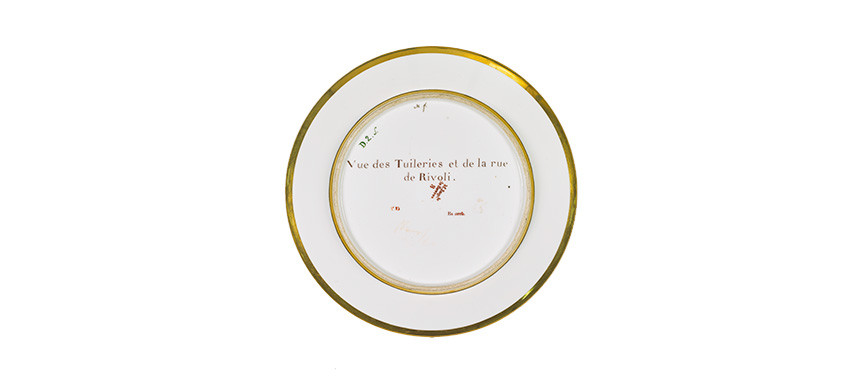

Nineteen plates from the Emperor’s personal service

1807-1811

Hard-paste porcelain

D. 24 cm

Inv. 30, acquired 1991, inv. 414 to 418 and inv. 792 A to M, donation Lapeyre

Having parted with the Olympic dinner service, presented to the Tsar, then with another known as the service “à zones d’or” to Caulaincourt’s embassy in Russia, Napoleon decided in October 1807 to commission a dinner service from the Sèvres manufactury which would be destined for the imperial table and known as the Emperor’s personal service. It was divided into four separate sets:

- a service for the first course consisting of 24 soup plates (1 at Fontainebleau), 8 butter dishes, 18 custard cups (pots à jus) and 4 salad bowls;

- a dessert service consisting of 24 serving dishes, 12 fruit dishes (2 at Fontainebleau), 4 ice-cream urns (3 at Fontainebleau), 4 sugar bowls (3 at Fontainebleau), 10 baskets of various sizes and a set of 72 richly painted plates, to which ours belong;

- a 25-piece biscuit table centrepiece (surtout) comprising 16 antique-style figures, a chariot drawn by two horses, and miniature candelabra, trivets, bowls and antique marble chairs (several items are at the Louvre museum) ;

- a “cabaret” set comprising 24 cups and saucers, 3 sugar bowls, a creamer and a milk jug, all decorated with views of Egypt and heads of oriental characters. Like part of the dessert service, this coffee service followed the emperor to St Helena (most of it is in the Louvre museum);

The cost of the whole service came to the princely sum of 65,449 F, compared with 53,400 F for the Olympic dinner service sent as a gift to Tsar Alexander in 1807.

These dessert plates from the Emperor’s personal service are also known as the “Quartiers Généraux” service, a name given them by the loyal valet Marchand at the moment of departure for St Helena, perhaps in reference to the headquarters occupied by Napoleon during his campaigns, a number of which are depicted on the plates. The service consists of 72 flat plates depicting various subjects, including 28 provided by Napoleon himself: 4 for both the Italian campaigns, 15 featuring the Egyptian campaign, 3 the Austrian campaign and the 6 others the campaigns in Prussia and Poland. The director of the manufactury, Alexandre Brongniart, assisted by Vivant Denon, completed the list with other key moments in these same campaigns, and with views of Paris, imperial residences, great institutions of the French Empire and major works completed in the provinces. Each plate costs 425 F, more expensive than anything else at that time. For the design on the rim (marli), a border of antique two-edged swords has been used, designed in April 1807 by the father of the manufactury’s director, architect Alexandre-Théodore Brongniart. The decision was finally made to use the colour chrome green, recently perfected by the chemist Vauquelin. The painters were able to begin work in January 1808 to finish in March 1810, just in time for the service to be delivered on 27 March to the Tuileries Palace to be used at the great banquet of 2 April to mark the marriage of the Emperor with Marie-Louise. Including the various gifts made by the emperor, which made it necessary to produce additional items to match, Sèvres completed a total of 82 plates, although the table at the Tuileries was never set with more than 72 at any one time. The work of the painters was divided between Jacques-François Swebach (27 plates), Nicolas-Antoine Lebel (20 plates), Jean-François Robert (20 plates), Christophe-Ferdinand Caron (9 plates), Pierre-Jean Boquet (2 plates), Jean-Claude Rumeau (2 plates), Jean-Louis Demarne (1 plate) and François Gonord (1 plate). The gilding on the friezes, costing 25 F per plate, was entrusted to François-Antoine Boullemier and to his son, Antoine-Gabriel, while the gilding on the ornamentation was the task of Pierre-Jean-Baptiste Vandé.

During the First Restoration, the 72 plates kept at the Tuileries were sent to Sèvres so as to grind off the inscriptions on the back along with the marks of the First Empire and replace them with the monogram of Louis XVIII, two Ls back-to-back painted in black. Napoleon was reunited with his service during the Hundred Days and, in June 1815, Fouché permitted him to take 60 plates to St Helena, the 12 others remaining at the Repository. The emperor did not use them at Longwood, keeping them to give as gifts to his entourage, so that by his death there were still 54 left. These plates were noticed by most of those present at St Helena. Bertrand recalls that after the death of the emperor, in accordance with the wishes of Lady Lowe, the furniture was replaced in the apartment and the porcelain plates displayed in the billiard room. Ali for his part, always precise in his descriptions, recounts how “at dinner [the emperor] would entertain himself by looking at the paintings on the plates of the fine Sèvres porcelain table service. I should point out that the Bourbons had had the monogram of Louis XVIII, back-to-back Ls, engraved on the bottom of these plates.” In an inventory dated 15 April 1821 appended to his will, Napoleon specifies: « 1° My medal. 2° My silverware and Sèvres porcelain which I used at St Helena. 3° I instruct Count Montholon to keep these items and pass them on to my son when he is sixteen years old.” Since the Court of Vienna had refused to accept this legacy, Montholon kept the plates and distributed them as he pleased; in 1851 the son of Las Cases still had 24 of them. Of the 19 plates belonging to the Fondation Napoléon, 15 were at St Helena, while the other 4 were sent by Napoleon in 1810 as gifts to his parents-in-law, the emperor and empress of Austria. The National Museum of Fontainebleau Palace has 22 on display, 9 of which are from the 12 retained in the Repository in 1815, one of these, broken, having been remade in 1824. 3 are kept at Malmaison Museum, 3 at the Royal Army Museum in Brussels, 2 at the Sèvres Museum, one at the Louvre Museum, one at the Napoleonic Museum in the Prince’s Palace at Monaco, and the others in private collections; only 8 plates remain unaccounted for.

Photographs © Fondation Napoléon